出町柳駅に降り立った朝、川面を渡る風がひんやりと頬を撫でた。

“大原‐比叡山‐坂本”へ、ここが今回の旅の始発点。

賀茂川と高野川が合わさるデルタを見渡すと、水のきらめきが目を射り、まるで旅の始まりを祝福してくれているようだった。

叡山電車に揺られて進むにつれ、町並みは後ろへと遠ざかり、窓の外には濃い緑が迫ってくる。

車両のきしむ音さえも、どこか心を弾ませる調べに聞こえてくる。

バスに乗り継いで第一の目的地「大原」に着くと、空気が一変した。

川のせせらぎ、鳥の声。参道に並ぶ漬物の樽からは、しば漬けの酸味ある香りが漂い、鼻をくすぐる。

苔むした石畳を歩き、木漏れ日の中にたたずむ三千院の山門をくぐった瞬間、時間の流れがやわらかく変わるのを感じた。

庭に腰を下ろすと、苔の絨毯に花びらがひらりと舞い落ちた。

微かな鐘の音が山に溶けていく。ここでは、自分の呼吸までもが自然の一部になる。

かつてこの大原は、若狭から京へと鯖を運んだ「鯖街道」のルートであった。

海の香りを背負った商人たちが峠を越え、この里に辿り着いたという。

その往来が生んだ賑わいの名残が、今も静かな山里の奥に潜んでいる。

藍色の木綿の着物をまとい、頭に手ぬぐいと柴の束をのせた一大原女(おおはらめ)。

その凛とした背中に、時代を超えた美しさと逞しさを感じた。

大原の空気は、どこか懐かしい。生と祈り、営みと静寂が、ひとつの呼吸に重なり合っているようだった。

大原を背に第二の目的地、「比叡山」へと向かう。

ケーブルカーが斜面を登るにつれ、木々のざわめきが耳を包み、肌を撫でる風が冷たさを増していく。

山頂に着くと、視界に広がったのは東にびわ湖、西に京の都。ふたつの景色を抱くその高さに、言葉を失った。

延暦寺の境内に足を踏み入れると、杉木立の間を霧が漂い、伽藍の屋根をやさしく包んでいる。

ここは天台宗の総本山、日本仏教の母山。

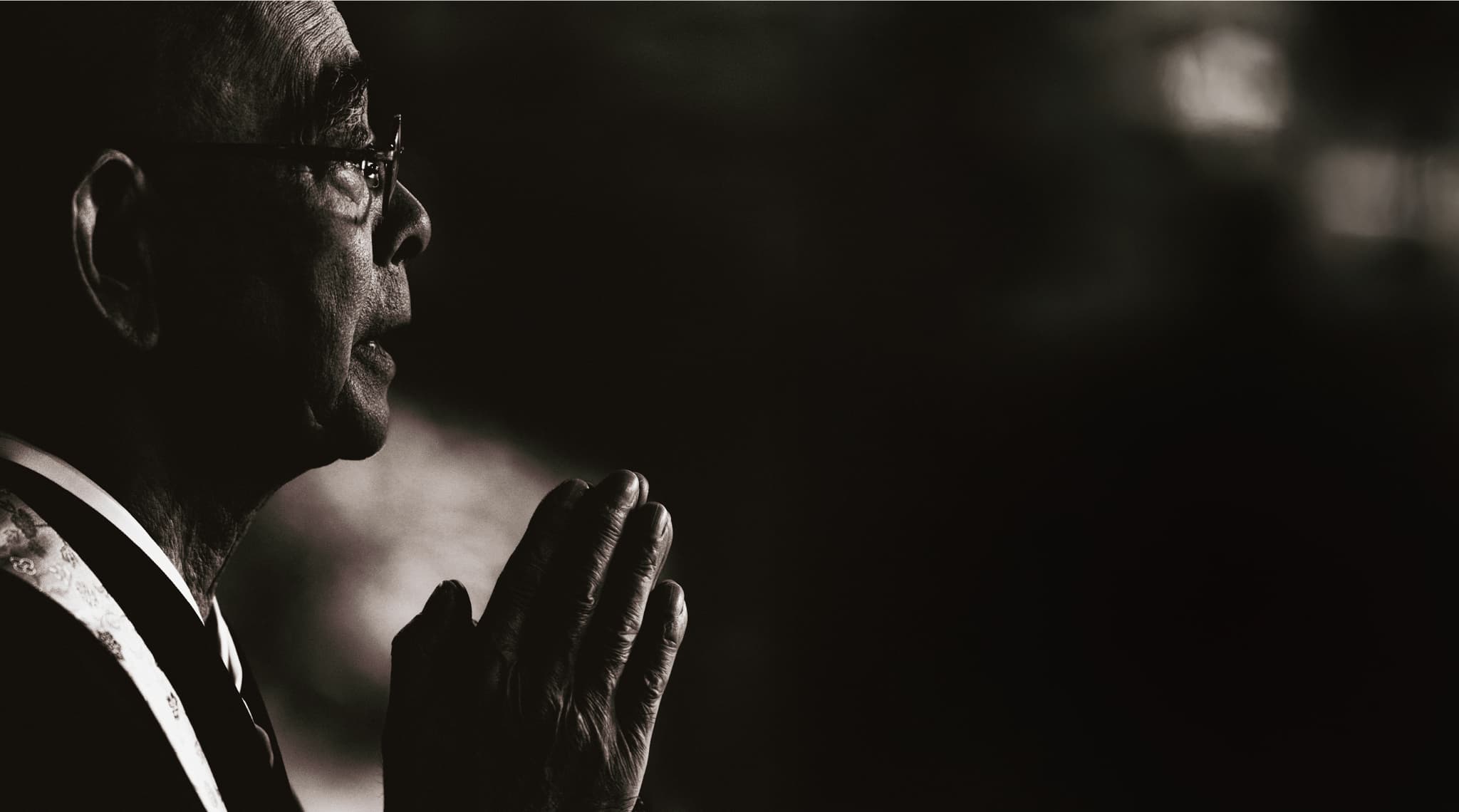

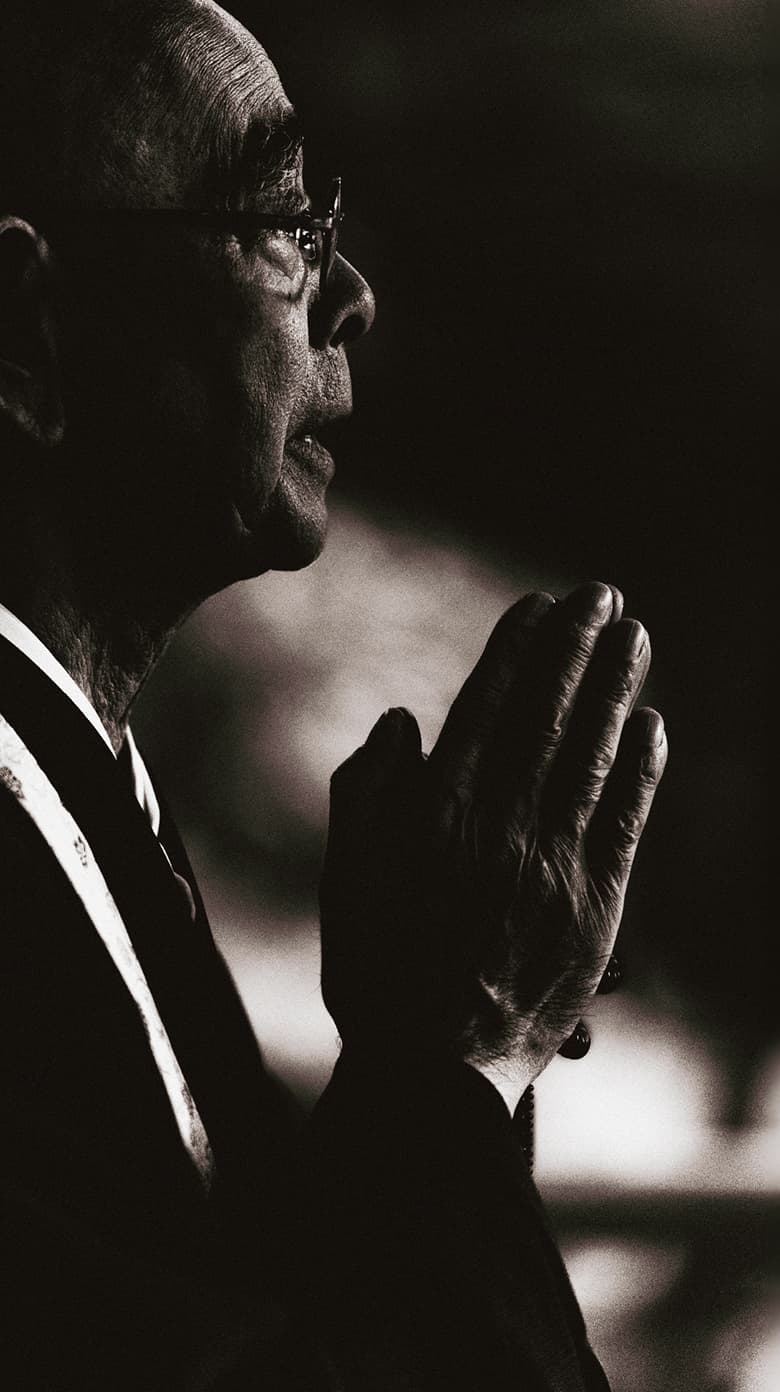

根本中堂の闇の中で揺れる「不滅の法灯」は、1200年以上燃え続ける祈りの象徴。

その炎を見つめていると、自分という存在が悠久の流れの中に静かに溶けていくのを感じた。

参道の脇には、厳しい修行に身を投じる行者たちの足跡が続いている。

千日回峰行――阿闍梨と呼ばれる行者が、祈りと苦行を繰り返しながら、自然と一体となるその姿を思い起こし、心が静かに震えた。

この山そのものが、一つの生きる経文のように思えた。

山を下り、坂本ケーブルに乗る。

日本一長い線路をゆっくりと進む車両の窓からは、びわ湖が青く輝き、まるで湖面に吸い込まれていくようだった。

第三の目的地、「坂本」の町に降り立つと、見事に積み上げられた石垣が迎えてくれた。

穴太積み――穴太衆の手による精緻な技。

自然石をそのまま生かして積む石垣は、400年を経た今も微動だにしない。

石を組む音が、遠い昔の鼓動のように今も大地に響いている気がした。

そして最後に訪れたのは、日吉大社。

朱塗りの楼門の奥には、千年の森が広がる。

日吉大社は比叡山の麓に鎮座し、約2100年前に創祀された全国3800余の分霊社の総本宮

――この杜は、延暦寺を護り、坂本の町を見守り続けてきた。

風が枝葉を揺らすたび、光が降り注ぎ、まるで山全体が祈っているかのようだった。

参道を歩くと、焼き団子の甘い香りが漂ってくる。一本手に取り、口に運ぶ。

香ばしさとともに広がる滋味が、旅の終わりをやさしく告げていた。

朝に出町柳で感じた風が、夕暮れの坂本でもう一度頬を撫でた。

そのとき気づいた。

この旅は、ただ道をたどったのではない。

大原の水音、比叡山の炎、坂本の石の冷たさ――そのすべてが、千年の歴史の呼吸として今も息づいている。

振り返ると、旅の余韻はまだ胸の奥で脈打っていた。

まるで比叡の山が、今もそっと語りかけてくるかのように。

Upon arriving at Demachiyanagi Station in the morning, a cool wind across the water surface gently brushed my cheek. The journey to “Ohara – Mount Hiei – Sakamoto” begins here. Looking out over the delta where the Kamo and Takano Rivers merge, the sparkle of the water hit my eyes, as if celebrating the start of the trip.

As the Eizan Electric Railway train rattled onward, the townscape receded, and thick greenery pressed in outside the window. Even the sound of the carriage creaking sounded like a tune that made my heart leap.

After transferring to a bus and arriving at the first destination, “Ohara,” the air completely changed. The babbling of the river, the sound of birds. From the pickle barrels lining the approach to the temple, the sour scent of shibazuke (pickled shiso eggplant) wafted, tickling my nose. Walking along the moss-covered stone path and passing through the Sanzen-in Temple gate, nestled in the sunbeams filtering through the trees, I felt the flow of time softly shift.

Sitting down in the garden, a flower petal fluttered down onto the carpet of moss. A faint sound of a bell melted into the mountains. Here, even my own breathing became a part of nature.

Ohara was once a route on the “Saba Kaido”(Mackerel Road), which transported mackerel from Wakasa to Kyoto.

The Oharame—women from Ohara—dressed in indigo cotton kimonos, with a head towel and a bundle of firewood on their heads. In their dignified posture, I felt a beauty and fortitude that transcended the ages.

The air of Ohara was somehow nostalgic. Life and prayer, daily work and stillness seemed to overlap in a single breath.

Leaving Ohara, I headed for the second destination, “Mount Hiei.” As the cable car ascended the slope, the rustling of the trees enveloped my ears, and the wind on my skin grew colder.

Upon reaching the summit, the view that unfolded before me was Lake Biwa to the east and Kyoto to the west. I was speechless at the height that embraced these two landscapes.

Stepping onto the grounds of Enryakuji Temple, mist drifted between the cedar groves, gently enveloping the roofs of the temple buildings. This is the head temple of the Tendai school of Buddhism, the mother mountain of Japanese Buddhism. The “Fumetsu no Hoto” (Inextinguishable Dharma Light) flickering in the darkness of the Konpon Chudo (main hall) is a symbol of prayer that has burned for over 1,200 years. Gazing at that flame, I felt my own existence quietly dissolving into the endless flow of time.

Beside the approach to the temple, the footprints of gyoja (ascetics) engaged in rigorous training continued. The Sennichi Kaihōgyō (Thousand-Day Circumambulation)—I recalled the sight of the ascetics called Ajari (Acharya) becoming one with nature as they repeated prayers and severe austerities, and my heart quietly trembled. This mountain itself seemed like a living sutra.

Descending the mountain, I took the Sakamoto Cable Car. From the window of the carriage, slowly moving along the longest line in Japan, Lake Biwa shone blue, as if I were being drawn into its surface.

Arriving in the town of “Sakamoto,” the third destination, I was greeted by magnificently piled stone walls. Anotsumi—the precise technique of the Anoshu stonemasons. The stone walls, built using natural stones as they were, remain completely stable even after 400 years. I felt as if the sound of the stones being set still echoed in the earth like a distant heartbeat.

The last place I visited was Hiyoshi Taisha Shrine. Beyond the vermilion-lacquered tower gate, a primeval forest spread out. Hiyoshi Taisha Shrine is situated at the foot of Mount Hiei and was founded about 2,100 years ago, serving as the Sohon-gu (head shrine) for over 3,800 branch shrines nationwide. This grove has protected Enryakuji Temple and watched over the town of Sakamoto. Every time the wind rustled the branches and leaves, light poured down, as if the entire mountain were praying.

Walking along the approach, the sweet scent of grilled dango (rice dumplings) wafted. I took one and brought it to my mouth. The savory flavor spreading with the aroma gently signaled the end of the journey.

The wind I had felt at Demachiyanagi in the morning once again brushed my cheek in the twilight of Sakamoto.

That’s when I realized. This trip was not just following a path. The sound of the water in Ohara, the flame on Mount Hiei, the coolness of the stone in Sakamoto—all of it is still alive as the breath of a thousand years of history. Looking back, the lingering feeling of the journey was still pulsing deep within my chest. As if Mount Hiei itself were still gently speaking to me.